Here's some useful information for river-based adventures using Magical Industrial Revolution. Skip to Part 3 or click this PDF link if you just want the rules.

Also, in case you missed the news, Magical Industrial Revolution is back in stock, with new sewn bindings and improved cover durability. (USA / CA / UK/EU)

Part 1: A Brief History of Steamboats

Well Admiral Fred, the garrison at the Burami Oasis is under constant siege. We're going to send a gunboat! [Cheers, whoops, applause, Land of Hope and Glory, etc.]

- The Goon Show, The Nasty Affair at the Burami Oasis, 1956

I. Full Steam Ahead

Before we get to the rules, it's worth reviewing a bit of real-world history.

Steam was certainly coming on water. The French had built a steamboat and tried it on the Seine as far back as 1775, but the power proved too weak; five years later, the Marquis Jouffroy d'Abbans went up the Saone near Lyons in a 182-ton paddle wheeler he called the Pyroscaphe. There were some American experiments in 1787, but Robert Fulton, who started to build steamboats when he returned to America in 1806, has the best claim to be the father of commercial steam navigation. His first patented boat, which had its trials on the East River on 9 August 1807, was described as “an ungainly craft looking precisely like a backwoods sawmill mounted on a scow and set on fire.” But it went 150 miles to Albany in only 32 hours, and back downriver in 30. Fulton was able to write in triumph: "The power of propelling boats by steam is now fully proved," adding, in the light of the Louisiana Purchase, "It will give a cheap and quick conveyance to the merchants on the Mississippi, Missouri and other great rivers which are now laying open their treasures- to the enterprise of our countrymen."

-Paul Johnson, The Birth of the Modern, pg. 195

Check out this excellent documentary from Part-Time Explorer for more information.

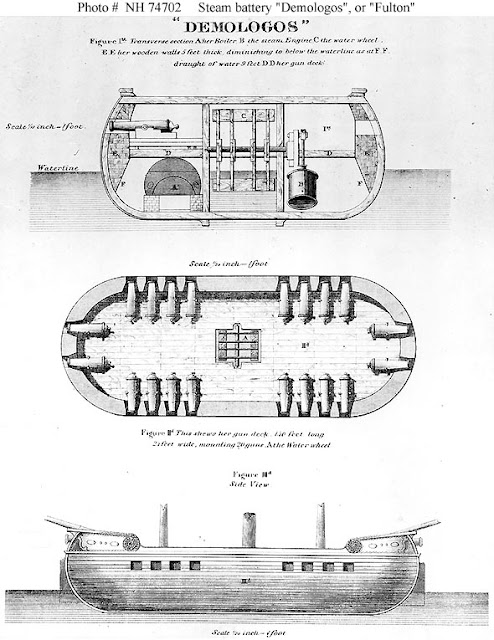

When the War of 1812 came, [Fulton] reverted in the most determined fashion to his earlier plan to annihilate the Royal Navy by high technology. This time, having been able to buy some powerful steam engines made by the leading British firm of Boulton & Watt, he concentrated on enormous, steam-driven surface warships. The project, variously christened Demologos (1813) and Fulton the First (1814), was a twin-hulled catamaran with huge 16-foot paddles between the hulls. It was 156 feet long, 56 wide, and 20 deep and protected by a solid timber belt nearly five feet thick. With an engine powered by a cylinder four feet in diameter, giving an engine-stroke of five feet, it was, in fact, a large armored steam warship. The British were also working on a steam-powered naval vessel, HMS Congo, which they were building at Chatham, but it was a mere sloop. Fulton's battleship carried thirty 32-lb guns firing red-hot shot and was also equipped to fire 100-lb projectiles below the waterline. With its 120 horsepower developing a speed of up to 5mph and independent of the wind, it theoretically outclassed any vessel in the British fleet.

Stories of this terrifying monster, which was launched on the East River on 29 June 1814, reached Britain and grew in the telling. The Edinburgh Evening Courant doubled the ship's size and credited her with 44 guns, including four giant 100-pounders. The newspaper added: "To annoy an enemy attempting to board it can discharge 100 gallons of boiling water a minute and, by mechanism, brandishing 300 cutlasses with the utmost regularity over her gunwales and works also an equal number of heavy iron pikes of great length, darting them from her sides with prodigious force. "

-Paul Johnson, The Birth of the Modern, pg. 15

A proper wizardly warship (as described in Edinburgh). The newspaper wasn't completely making things up... just mostly making things up.

Room is left for a machine which Fulton purposed to add, capable of discharging with great force an incessant stream of water either hot or cold, which it was anticipated would completely inundate an enemy’s armament and ammunition, if it did not also destroy the men. Our newspapers, copying the marvellous reports which were afloat respecting her, assured their readers that this non-descript man of war was to brandish along its sides some hundreds of cutlasses and boarding pikes, and vomit boiling pitch on her unfortunate antagonists; these however are poetical exaggerations.

-John M. Duncan, Travels through Part of the United States and Canada in 1818 and 1819, Volume I, pp. 35-41, via.

Steam, a boon in so many ways, created brand-new perils, especially on the rivers it queened. Up to the 1840, nearly one-third of the Mississippi steam boats were lost in accidents. Burst boilers were so common – 150 were recorded up to 1850, with 1,400 killed; the real total was much higher – that Charles Dickens, for instance, was strongly advised to sleep at the back of the boat. In February 1830 the Helen McGregor was leaving Memphis, Tennessee, when the head of her starboard boiler cracked, and the explosion killed 50 souls, flayed alive or suffocated inhaling the steam. All the same, the number of those lost at sea, as a proportion of those traveling, began to fall steadily after 1815.

-Paul Johnson, The Birth of the Modern, pg. 200

The real total being higher refers to both inadequate record-keeping and the fact that some people aboard were counted as cargo. In chapter 49 of Life on the Mississippi, Mark Twain lists all the former colleagues and old friends blow up or lost in various accidents.

II. The Riverboat Sails Tonight

Drays, carts, men, boys, all go hurrying from many quarters to a common center, the wharf. Assembled there, the people fasten their eyes upon the coming boat as upon a wonder they are seeing for the first time. And the boat is rather a handsome sight, too. She is long and sharp and trim and pretty; she has two tall, fancy-topped chimneys, with a gilded device of some kind swung between them; a fanciful pilot-house, a glass and 'gingerbread', perched on top of the 'texas' deck behind them; the paddle-boxes are gorgeous with a picture or with gilded rays above the boat's name; the boiler deck, the hurricane deck, and the texas deck are fenced and ornamented with clean white railings; there is a flag gallantly flying from the jack-staff; the furnace doors are open and the fires glaring bravely; the upper decks are black with passengers; the captain stands by the big bell, calm, imposing, the envy of all; great volumes of the blackest smoke are rolling and tumbling out of the chimneys—a husbanded grandeur created with a bit of pitch pine just before arriving at a town; the crew are grouped on the forecastle; the broad stage is run far out over the port bow, and an envied deckhand stands picturesquely on the end of it with a coil of rope in his hand; the pent steam is screaming through the gauge-cocks, the captain lifts his hand, a bell rings, the wheels stop; then they turn back, churning the water to foam, and the steamer is at rest. Then such a scramble as there is to get aboard, and to get ashore, and to take in freight and to discharge freight, all at one and the same time; and such a yelling and cursing as the mates facilitate it all with! Ten minutes later the steamer is under way again, with no flag on the jack-staff and no black smoke issuing from the chimneys. After ten more minutes the town is dead again, and the town drunkard asleep by the skids once more.

-Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi, ch.4

Why not check out a 1928 public domain film involving a riverboat? That's right, Buster Keaton's Steamboat Bill, Jr.

I bet you thought I'd mention that damned mouse, didn't you? For shame. Steamboat Bill, Jr. is 55 minutes of fairly standard but enjoyable silent movie gag, followed by 13 minutes of "how the hell did they do that?" stunts. (Spoiler alert: the answer is "six truck-mounted liberty plane engines.")

III. Our Superior Technology Will Solve The Problem (This Time)

Early in 1825, nearly 500 miles up the River Irrawaddy in Burma, a curious battle took place between the new and the old world, when the East India Company's steam warship Diana chased a Burmese imperial war prau up-river. These praus were perhaps the most fearful oar driven craft ever devised. They carried a mass of fighting men and were driven at seven to eight miles an hour by 100 double-banked oars, wielded by highly trained oarsmen. In their river environment they were just as formidable as the vast triremes of antiquity, and they enabled the kings of Burma to pursue an aggressive policy of expansion over a large part of Southeast Asia and up along the Bay of Bengal. Captain Marryat, who watched their performance from the Larne sloop of war, which he commanded, pronounced them "Very splendid vessels." But Marryat, who commanded the naval forces in the First Burma War, was also responsible for bringing the Diana into Burmese waters. He was the first to grasp the vital point that shallow draft steam-powered vessels, whether paddle or screw, were ideally suited to river warfare.

The Diana had been launched at Kiddapore in 1823. She had paddles driven by a 60-horsepower engine, which would burn either coal or wood. As a result, she was almost self-fueling for jungle-river work; she had merely to pull into the side while her crew cut timber. Moreover, her own engineers could service and, if necessary, repair her simple power unit and for eight years she never had to go into dock. Marryat insisted on taking the Diana as part of his force, for she could tow a train of troop-carrying vessels up-river whether or not there was any wind. What he did not foresee, until it happened, was that she would prove a decisive weapon against the giant war praus. She simply put on full power and chased the praus up river. After four or five hours of continuous cowing, the Burmese oarsmen collapsed (in some cases, died) from exhaustion, and once the prau was stationary, it was holed and sunk at leisure by the Diana's deck guns. The Diana, in fact, was the first modem gunboat, and she introduced the era of gunboat diplomacy. As one observer, describing the steam-oar race to the death, put it: “The muscles and sinews of men could not hold out against the perseverence of the boiling kettle.”

The performance of the Diana was widely noted, and conclusions were drawn all over the world. In China, which in 1829 saw the first Western steamboat the Forbes, also built at Kiddapore, William Jarndyce recognized the capacity of the sreamboat to push up and dominate China's great rivers in ways that no sailing warship dared risk. "A few gunboats alongside this city,” he wrote from Canton, where the follies, corruption, and cruelty of the regime was becoming daily more apparent, would overrule any "caprice" of the local authorities by "the discharge of a few mortars.”

In large parts of Asia and Africa, the arrival of military steam power was felt by many Westerners, for altruistic as well as commercial reasons, to be an almost divine deliverance, a means whereby the horrors and oppressions of native rulers could be brought to an end. In West Africa, Robert Macgregor, one of the men behind the first great Niger expedition (1832-34), noted: “By [Watt's] invention every great river is open up to us." He saw not just the Mississippi, but "the Amazon, the Niger and the Nile, the Indus and the Ganges" mastered "by hundreds of steam-vessels, carrying the glad tidings of 'peace and good-will to all men' into the dark places of the earth which are now filled with cruelty." In many cases, those who were most anxious to use the new gunboats were the missionaries who wanted to end slavery, cannibalism, human sacrifice, and other unspeakable evils. They were inclined to see the hand of the Almighty in the emergency of naval steam technology.

-Paul Johnson, The Birth of the Modern, pp. 789-791

"In many cases..." is further weaseling from Johnson. I might write a full review of the book at some point, but let's just say it's a trend. In many other cases, of course, people anxious to use the power of steam didn't have altruistic goals in mind. Shocking, I know. As Thomas Carlyle said of Adolphe Theirs, Johnson is "a brisk man in his way, and will tell you much if you know nothing."

How solemn and beautiful is the thought, that the earliest pioneer of civilization, the van-leader of civilization, is never the steamboat, never the railroad, never the newspaper, never the Sabbath-school, never the missionary—but always whiskey! Such is the case. Look history over; you will see. The missionary comes after the whiskey—I mean he arrives after the whiskey has arrived; next comes the poor immigrant, with ax and hoe and rifle; next, the trader; next, the miscellaneous rush; next, the gambler, the desperado, the highwayman, and all their kindred in sin of both sexes; and next, the smart chap who has bought up an old grant that covers all the land; this brings the lawyer tribe; the vigilance committee brings the undertaker. All these interests bring the newspaper; the newspaper starts up politics and a railroad; all hands turn to and build a church and a jail—and behold, civilization is established for ever in the land. But whiskey, you see, was the van-leader in this beneficent work. It always is. It was like a foreigner—and excusable in a foreigner—to be ignorant of this great truth, and wander off into astronomy to borrow a symbol. But if he had been conversant with the facts, he would have said— Westward the Jug of Empire takes its way.

-Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi, ch.4

Part 2: Rivers and Pirates

Piracy is the carcinization of RPGs. It's a long-standing truism that, given access to a boat, the PCs will drop everything, sail over the horizon, and become pirates, burning merchant ships and your campaign notes at the same time.

These days, you can't avoid it by setting your campaign inland. Between Luka Rejec's Ultraviolet Grasslands and Sam Sorensen's Seas of Sand, the piratical urge can strike anywhere.

River adventures offers a compromise between open oceanic piracy and a traditional hex/pointcrawl. You can't completely sail away from your problems on a river, but, if the river is wide, messy, and changeable, you can evade them. Run up branches, hide in swamps, tie up on the wrong side of an island and cover your boat in branches, etc. Deal with the usual problems (factions, weather, crocodiles, advanced crocodiles, etc.)

I. The Unexplored Hinterland (Or: Where is Endon?)

Endon, as written, is a city-state with a heavy emphasis on "city." I didn't want to write a colonial city with possessions and interests if I couldn't devote sufficient time and detail to the other side of the equation. It didn't feel right, or fair, or useful. Endon is designed to be plonked into an existing setting, ready to cause trouble and bend the setting around it, like a red-hot marble on a rubber sheet.

The River Burl bisects Endon. The sea is somewhere downstream, but, if you wanted to run a steamboat campaign, upstream could be lightly explored (read: exploited) territory. Not a true wilderness, but a collection of literal backwaters (from Endon's point of view), ready to receive the Benefits of Civilization, Free Trade, and Modern Magic... or else. The PCs' opinions of those capital-letter values may vary.

If the idea an "unexplored" Thames or Forth seems ludicrous, there's always the Hudson or the Volga.

For the Russians, the fur trade and conquest were identical. The government was the chief fur trader and exacted fur tribute from conquered natives. It authorized private traders but had an option on their best furs and taxed the rest at 10 percent. The stale church reinforced government power. The fur trade was enormously lucrative, acting as a sharp incentive both to the state and to private colonizers. One black fox pelt would buy a plot of over 50 acres, pay for the erection of a cabin and stock of up to 5 horses, 20 cattle, 20 sheep, and fowls. In time the portage system was replaced by canals. The earliest, 1703-09, was the Upper Volga Waterway, which linked its higher reaches to the Baltic. But the explosion of river transport, as in the West, came in the early 19th century. By then the waterway was carrying 5,000 boars a year, and it was soon joined by the Narvsky System (1808), another route to the Gulf of Finland, the Tikhvin Waterway (1811), linking the Mologa, a Volga tributary, to the Siaz, which flows into Lake Ladoga, and the Northern Dvina system, built 1824-28. By 1830 the Volga, which has a basin of 1,080 rivers, streams and lakes, was effectively canalized, linking the river systems of Eastern Europe to Russian Asia. As a result, the European population of Siberia began to increase rapidly. In 1724 it was counted at a mere 400,000. By 1858 it was 2.3 million, mostly Russian settlers, harbingers of an even grater migration of 5 million, nearly all of them peasants, which by 1911 had transformed the demography of this vast portion of the Earth's surface and made it 85 percent Russian.

-Paul Johnson, The Birth of the Modern, pg. 269

II. Starting Points and Prompts

A steamboat can be a way to integrate standard dungeon-crawling adventures with Endon, as well as providing the players with a mobile base/fortress.

"We found a strange underground structure while cutting a new canal / building a trading post / prospecting / evicting the locals" is a way to add the dungeoncrawl gameplay loop to Endon. Integrate the cutters from Incunabuli. Invent ancient empires (or perfectly functional current empires that haven't invented the steamboat and the high-velocity cannon), tombs (of "raaather eccentric" country squires or prehistoric soldiers), etc.

"Everyone else on your ill-equipped expedition has died of new and horrible diseases" is a good start.

Marryat was often ill with fever, and he was bitterly critical of the authorities who could send men on this kind of expedition without any attempt to provide them with suitable tropical uniforms, mosquito netting, and antimalarial stores. There was no milk, fresh meat, fish, fruit, or vegetables, only salt pork and biscuits. By the end of 1824, of the 3,586 whites in the original force, 3,115 were dead. Marryat believed that it was only the superiority of British weapons that gave them victory.

-Paul Johnson, The Birth of the Modern, pg. 793

From lead-lined tins to cheaper limes, there are plenty of ways some far-off bureaucrat can sink an expedition and, through attrition, put people like the PCs in charge.

"Generic D&D adventurers from a sleepy river town see a steamboat for the first time" also works. Endon has arrived! Cheap goods for all (if you can pay in gold, silver, gems, or Endon's currency.) By the way, do you have any old magic items, spells, or minerals lying around the place? No reason. We're just curious.

Part 3: Send a Gunboat

I've created a free 8-page PDF with some useful tables, rules, and prompts. It includes:

- Rules for building your own steamboat.

- Firearms, from muskets to cannons.

- Trade goods.

- A river system generator.

- Plot seeds for river adventures.

Enjoy!

This is great! I especially like the listed supplements and plot seeds. (You're good at those.)

ReplyDelete> If the idea an "unexplored" Thames or Forth seems ludicrous, there's always the Hudson or the Volga.

ReplyDeleteYou could always have an unexplored Thames anyway. Savage wilderness full of untold treasures, suburban Maidenhead, really, what's the difference?

...actually, having written this down, the, shall-we-say, precarious state of scientific/magical inquiry in this setting has probably made the Oxford equivalent a bit of a lost city, hasn't it? Spires dreaming unsavory dreams...

Anyway, great stuff. Interesting to see more colonialism creeping into Endon, and by extension more opportunities for PCs to be fish out of water.

i linked this on my river travel post on elfmaids & octopi

ReplyDeletesaved me some work for my next game

ill get the big book when i can afford postage

Since Russian fur prices came up in this post, there's a nice paper on JSTOR about them here: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24656503

ReplyDeleteLong story short: black fox was really expensive. The average price was 11.33 rubles. The rest of the top five most expensive furs were black beaver (3.58 rubles on average), bobcat (3.50), beaver (2.09), and sable (1.77). One ruble was 48 grams of silver, so the average black fox fur sold for a little more than 19 ounces of silver.

Love it. Just a word on timber as armour: When I was visiting the Jylland up in Denmark they had a video showing the testing of a period-appropriate cannon (1860ish) against that ships hull (I believe around 150cm of oak plus some metal sheeting). Went right through. Small impact on the outside, hellstorm of wood shrapnell on the inside. There were battle reports from the ship of entire gun crews (like over a dozen people) turned into bloody mulch by impacts from cannon fire during the battle of Heligoland 1864. Just my thoughts when I read about the Demologos.

ReplyDelete150cm sounds like a lot for the Niels Juhl-class Jylland. The British Imperieuse-class frigates, which were roughly the same size as Jylland and started being built 4 years before the Niels Juhl, had a hull that was around 150mm thick, or 15cm.

Delete