Actually, I should clarify. It is difficult to make medieval medicine gameable in an OSR context. Systems of diagnosis and treatment are too complex to replicate without pages and pages of explanatory text on historical or fictional notions. Adding complexity to the healing process in RPGs seems to just slow down access the "interesting" part of games. Nobody turns up to game to roll on the "hemorrhoid treatment progress" table.

So instead of trying to come up with a "Doctor" class, I've put a few miscellaneous and interesting quotes and observations in this article. Enjoy!

|

| Chirurgia, Roger of Salerno. Christ the Physician applies several treatments. |

The Nature of Suffering

Suffering purifies the soul, or so Christian theology said. The body is a corrupt vessel. Why bother maintaining it, clothing it in soft cloth, feeding it delicious food, and gratifying carnal desires when they might impede progress towards eternal bliss? If you become diseased, it's because you are being tested or punished. Accept it.On the other hand, Christ - the heavenly leech of the title - healed the sick, so clearly suffering isn't entirely laudable. And aside from a few saints, most people, when faced with disease or injury, sought treatment of some sort. Virtuous suffering is easy until you have to pass a kidney stone.

If treatment was unavailable or ineffectual, victims could console themselves with theology.

But if we not only hear this word "death," but also let sink into our hearts the very fantasy and deep imagination thereof, we shall perceive thereby that we were never so greatly moved by the beholding of the Dance of Death pictured in Paul's, as we shall feel ourselves stirred and altered by the feeling of that imagination in our hearts. And no marvel. For those pictures express only the loathly figure of our dead bony bodies, bitten away the flesh; which though it be ugly to behold, yet neither the light thereof, nor the sight of all the dead heads in the charnel house, nor the apparition of a very ghost, is half so grisly as the deep conceived fantasy of death in his nature, by the lively imagination graven in thine own heart. For there seest thou, not one plain grievous sight of the bare bones hanging by the sinews, but thou seest (if thou fantasy thine own death, for so art thou by this counsel advised), thou seest, I say, thyself, if thou die no worse death, yet at the leastwise lying in thy bed, thy head shooting, thy back aching, thy veins beating, thine heart panting, thy throat rattling, thy flesh trembling, thy mouth gaping, thy nose sharping, thy legs cooling, thy fingers fumbling, thy breath shortening, all thy strength fainting, thy life vanishing, and thy death drawing on.

If thou couldst now call to thy remembrance some of those sicknesses that have most grieved thee and tormented thee in thy days, as every man hath felt some, and then findest thou that some one disease in some one part of thy body, as percase the stone or the strangury, have put thee to thine own mind to no less torment than thou shouldst have felt if one had put up a knife into the same place, and wouldst, as thee then seemed, have been content with such a change -- think what it will be then when thou shalt feel so many such pains in every part of thy body, breaking thy veins and thy life strings, with like pain and grief as though as many knives as thy body might receive should everywhere enter and meet in the midst.

A stroke of a staff, a cut of a knife, the flesh singed with fire, the pain of sundry sickness, many men have essayed in themselves; and they that have not yet, somewhat have heard by them that felt it. But what manner dolor and pain, what manner of grievous pangs, what intolerable torment, the silly creature feeleth in the dissolution and severance of the soul from the body, never was there body that yet could tell the tale.

-Thomas More's Last Things.

Side Note: I normally use translated or transliterated primary sources on this blog, but the original text is worth reading:

I saye, thy selfe yf thou dye no worse death, yet at the least lying in thy bedde, thy hed shooting, thy backe akyng, thy vaynes beating, thine heart panting, thy throte ratelyng, thy fleshe trembling, thy mouth gaping, thy nose sharping, thy legges coling, thy fingers fimbling, thy breath shorting, all thy strength fainting, thy lyfe vanishing, and thy death drawyng on.The next time you're ill, be sure to describe your symptoms in these terms.

Since immorality and selfishness caused disease, it followed logically that righteous living would not only be good for the immortal soul but also likely offer immunity against earthly pestilence. As San Bernardino urged his Italian congregations in the early fifteenth century, charity rather than physic should be there first resort during epidemics; there could be no better preventative medicine than almsgiving, which pleased God and disposed him, in turn, to show compassion. But knowing from personal experience that generosity alone could not guarantee survival, or ease the spots and stains of sin, medieval men and women also sought to safeguard their physical, as well as spiritual health, through prayer and pilgrimage.

[...]

The rich might choose to pay for special masses to be said during epidemics; or secure for themselves the promise of a year free from the malign effects of 'want, emptiness, loss of cattle, fumes and evil vapours, cramps, dropsy, cancer, leprosy, asthma, unclean spirits, shame, bad luck... water, fire, lightning, tempest, plague, and sudden death' simply by fasting on bread and water and having a mass of St Anthony said on their behalf.

-Medicine & Society in Later Medieval England, Carole Rawcliffe

High Mortality

The myth of 40 being old age has been so thoroughly demolished it's barely a myth anymore. Infant mortality skews the average downwards, and infants died in all sorts of horrible ways. Aside from the usual infections, poisons, and fires, anyone who raised both pigs and children took a chance. Open wells, mad dogs, ponds, woodpiles, and wagons claimed their share.Chances are good your everyone in your class on your first day of school was/will be alive when you turn/turned 20. Death, in the modern west, is a rare and tragic event. In medieval Europe, death was a constant companion, even in periods without sweeping epidemics. PCs in OSR-type games are often a bit blase about the tragic demise of their companions. I'm not sure that's a problem.

Pain Relief

There's a persistent idea that pain relief, aside from alcohol, wasn't available in medieval Europe. This isn't true. It was easy, even trivial to make sleeping draughts and soporifics.It was very difficult to make sleeping draughts and soporifics that didn't kill their victims.

The two main ingredient of powerful medieval soporifics, opium and hemlock, could easily be lethal. Proportions were given in widely varying measures. Freshness of ingredients, or even their local name, also defied standardization. But there's a sort of brilliant logic to medieval draughts. They typically contained a soporific (alcohol, henbane, opium, lettuce, and/or hemlock) and a laxative or emetic (henbane, briony, gall, wine). The patient would be rendered insensible by the potent soporific, but, ideally, the drug would pass from their system one way or another before permanent harm resulted.

Side Note: yes, lettuce used to be mildly soporific.

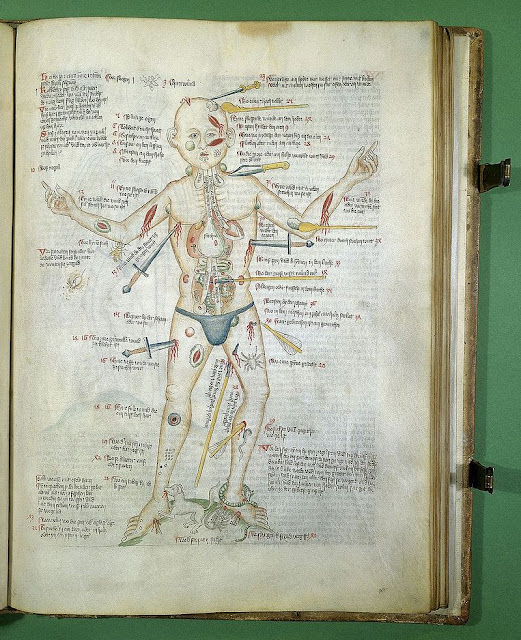

|

| Wound Man, the medieval superhero. |

Oof Ouch My Bones

Medieval medical theories (below) might be obtuse, but battlefield surgery tends to sweep away theories and focus on practical results.

Removing a dart or arrowhead before the wound became critically infected was a difficult task. Hammers, tongs, and curses were commonly employed. If possible, removal was postponed until a natural cyst formed around the foreign body. Styptics of dried egg and resin helped with external bleeding where cauterization was not possible, and stitches helped close wounds, but serious internal injuries were often beyond a surgeon's power.

Skilled medieval surgeons managed to perform cataract surgery without anesthetic, bright artificial lights, or stainless steel. Thick ropes and strong servants, recommended by medical textbooks, helped.

The Death and Dismemberment and Disfigurement Table

A classic Death and Dismemberment table should include some hideous wounds.An examination of the skeletal remains of Sigh Hugh Hastings, a Norfolk Landowner who died in 1347 aged less than forty, reveals that he suffered from osteoarthritis, probably caused by continuous practice with a broad-sword or other heavy weapon, and compounded by the physical wear and tear of military campaigns in France. Although he was the son of a nobleman and had spent time at Court, he evidently consumed coarse bread containing particles of grit (of the sort eaten by the peasantry), which had caused progressive dental deterioration. A blow to the mouth had, moreover, deprived him of at least five or six front teeth, so that by the time of his death he must have found eating very difficult indeed.

Facial disfigurements were by no means uncommon during this period: the heroes of one of the most popular chivalric romances of the fifteenth century, Le Mort d'Arthur, regularly identify each other by their most recent wounds; and in this respect, at least, the author (who must have sustained quite a few cuts and bruises during the course of his own turbulent career) seems to have been drawing on personal experience. We know that in 1374 a quarter of recruits serving in the Provencal army were badly scarred on the hands or face; and that many English soldiers mutilated in the wars with France returned home in a parlous condition to beg. Even allowing for the exaggeration common in such cases, we cannot but marvel at the powers of survival mustered by one Thomas Hostell, whose misfortunes had begun in 1415 at the siege of Harfleur. There he had been

smyten with a springolt through the hede, lesing his oon ye, and his cheke boon broken; also at the bataille of Agingcourt, and after at the takyng of the carrakes on the see, there with a gadd of yren his plates smyten in sondre, and sore hurt, maymed and wounded; by meane wherof he being sore febeled and debrused, now falle to great age and poverty, gretly endetted, and may not helpe himself.

-Medicine & Society in Later Medieval England, Carole RawcliffeOr if you'd prefer a modern source:

A lot of rural people in Iowa in the fifties had arresting physical features - wooden legs, stumpy arms, outstandingly dented heads, hands without fingers, mouths without tongues, sockets without eyes, scars that ran for feet, sometimes going in one sleeve and out the other. Goodness knows what people got up to back then, but they suffered some mishaps, that's for sure.

-The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid: A Memoir, Bill Bryson

The 4 Humours

Straight from Wikipedia:| Humour | Season | Ages | Element | Organ | Qualities | Temperament |

| Blood | spring | infancy | air | liver | warm and moist | sanguine |

| Yellow bile | summer | youth | fire | gallbladder | warm and dry | choleric |

| Black bile | autumn | adulthood | earth | spleen | cold and dry | melancholic |

| Phlegm | winter | old age | water | brain/lungs | cold and moist | phlegmatic |

But that's boring and dry. Instead:

Sanguineus:

Of yiftes large, in love hath grete delite,

Iocunde and gladde, ay of laughing chiere

Of ruddy colour meyne somdel with white;

Disposed by kynde to be a champioun

Hardy i-nough, manly, and bold of chiere.

Of the sangwyne also it is a signe,

To be demure, right curteys, and benynge.

Colericus:

The coleryk: froward and of disceyte,

Irous in hert, prodigal in expence,

Hady also, and worchith ay by sleyght.

Sklendre and smalle, ful light in existence,

Right drye of nature for the grete fervence

Of heet; and the coleryk hath this signe,

He is comunely of colour cytryne.

Fleumaticus:

The flewmatyk is sompnelent and slowe,

With humours grosse, replete, ay habundaunt,

To spitte invenons the flewmatic is knowe,

By dulle conceyte and voyde, unsufficiaunt

The sutill art to complice or haunt;

Fat of kynde, teh flewmous, men may trace,

And know hym best by whitness of his face.

Malencolicus:

The malencolicus thus men espie:

He is thought and sette in covetise,

Replenysshith full of fretyng envye;

His hert servith hym to spende in no wise,

Trayterous frawde full wele can he devise;

Coward of kynde when he shuld be a man,

Thow shalt hym knowe by visage pale and wan.

-The Four ComplexionsHumorial theory was the core of theories about the body. Diseases caused an imbalance in the body's humours; a physician could, by applying the correct treatment, drug, diet, or environment, correct this balance. It was rarely as simple as an excess or defect of one humour. Instead, the complex interplay of age, location, organ, diet, and personal balance contributed to the balance and dictated the necessary treatment.

Since virtually every condition and treatment could be described in these terms, humorial theory flourished. It is a perfect self-contained paradigm; any challenges are absorbed without disturbance. Since the human body can recover from many injuries without (or in spite of) the aid of dubious medicines, the theory seemed to be successful.

Practical preventative medicine focused on simple and recognizable advice: eating sensible portions with fresh vegetables and fruit, regular sleep and exercise, avoiding conflict and stress, moderate drinking, and quiet living. Then as now, people tended to ignore this advice and do whatever they wanted.

Off To See The Whizzard

|

| Gunshow |

Now in every man is body is foure qualitees: hete and colde, moyste and drye. Hete and colde they ben causers of colours. Drynes and moystene they ben causes of substance. Hete is cause of rede colour; drynes is cause of thyn substance; moystenes is cause of thycke substaunce. And thus, if the uryn of the pacient be rede and thicke it signifieth that blode is hote and moyste. If it be rede and thyne hit sheweth that colere hath dominacioun, ffor why colere is hote and drye. If the uryn appere white and thicke hit betokeneth fleume, ffor fleume is colde and moyste. If the uryn appere white and thynne, it signifieth malencoly, ffor malencoly is colde and drye. Then thu hast considerid wel as this, then beholde the diversite of colours of the uryns.. .

-Wellcome Library, Western Ms, 537 ff. 16-16v, quoted from Medicine & Society in Later Medieval England, Carole Rawcliffe

Uroscopy allowed discreet analysis at a distance. Rich patients dispatched daily urine samples to distant physicians, who sent back daily advice or reassuring notes. Fortified with charts and frequent practice, physicians felt reasonably confident in their diagnoses, and experienced practitioners probably drew reasonable conclusions about the heath of their patients. Analysis of blood, feces, and sweat was also encouraged.

If anyone feels like making this gameable, they're on their own.

Practical Medicine

Treating humorial imbalance according to the complex instructions of medical authorities was rarely practical or affordable. Physicians used their judgement, and a healthy dose of practical folk remedies, where more complex cures failed.Some cures seemed worse than the disease.

Note, it is necessary for lethargics, that people talk loudly in their presence. Tie their extremities tightly, rub their palms and soles hard; and let their feet be put in salt water up to the middle of their shins, and pull the hair and nose, and squeeze the toes and fingers tightly, and cause pigs to squeal in his ears; give him a sharp clyster [enema] at the beginning... and open the vein of the head, or nose, or forehead, and draw blood from the nose with the bristles of a boar. Put a feather, or a straw in his nose to compel him to sneeze, and do not ever desist from hindering him from sleeping; and let human hair, or other evil-smelling thing, be burnt under the nose. Apply moreover the cupping horn between the shoulders, and let a feather be put down the throat, to cause vomiting, and shave the back of the head, and rub oil of roses and vinegar, and smallage juice thereon.That'll cure your lethargy, if only to get away from your physician.

-Rosa Anglica

Bloodletting, as a preventative measure as well as a cure, was very popular. Unlicensed and lightly trained phlebotomists were widely available. Healthy and hearty people chose auspicious days for bloodletting; the sick, aged, or infirm sought it as a last resort. As no effective methods for stopping blood flow existed, accidental deaths were common, but the practice seemed to carry significant benefits. It's well known that the more invasive and impressive a placebo is, the greater its effects. A placebo injection carries more weight than a placebo pill.

At the Augustinian priory of Barnwell, in Cambridgeshire, for instance, the brothers were bled on average seven times a year, being allowed to take three days' rest in the infirmary on each occasion. Since they were exempted from the punishing round of liturgical practice, allowed a more generous and nourishing diet than usual and permitted to take as much gentle exercise as they wished, it is easy to see why they felt much better afterwards.If direct bloodletting was too dangerous, leeches or cupping were available. Cauterization, burning infected flesh or creating new wounds to remove superfluous cold or moist humours, was also common. A treatment for "stubborn headaches, dropsy, epilepsy, disorders of the eyes, throat, nose and ears, coughs, nosebleeds, and 'flux of the wombe that cometh of the reume' went as follows:

-Medicine & Society in Later Medieval England, Carole Rawcliffe

bid the patient open the bowels with an evacuant which will also clear his head, for three or four nights, according to the strength, age, and habits of the patient. Then tell him to have his head shaved; then seat him cross-legged before you, with his hands on his breast. Then place the lower part of your palm on the root of his nose between his eyes; and where your middle finger reaches mark that place with ink. Then heat an olivary cautery. Then bring it down upon the marked place with one downward stroke of gentle pressure, revolving the cautery; then quickly take your hand away while observing the place. If you see that some bone is exposed, the size of the head of a skewer or a grain of vetch, then take your hand away; otherwise repeat with the same iron or, if that has gone cold, with another, till the amount of bone I have mentioned is exposed. Then take a little salt in water; soak some cotton in it, apply it to the place, then leave it for three days.

-Albucasis, quoted in Medicine & Society in Later Medieval England, Carole RawcliffeCauterizing the head or limbs was merely agonizing. Cauterizing the neck or torso was more dangerous, and could, if done improperly, cause the patient to burst.

|

| The Baby-Eating Bishop of Bath and Wells |

Treacle

To most people, "treacle" is molasses or golden syrup; a thick sugary liquid that belongs in the kitchen, not the pharmacy.

But in late medieval Europe, treacle (or theriac), was the most potent cure on the market. It was hailed as a panacea, a universal cure. Applied internally or externally, in small or large doses, it was the preferred treatment of anyone who could afford it.

Treacle was compounded and aged according to a variety of ancient recipes. On the principle of opposition, treacle was made partially of known poisons, so better to counteract other poisons. The flesh of vipers was a common ingredient, but the general principle seemed to be to be to mix every known medical or pseudomedical ingredient in honey. Like the ingredient list of a modern energy drink or some fictitious drugs, a little bit of everything was thought to help.

Transport from its point of origin in Italy or Greece to Europe afforded many opportunities for adulteration or dilution, so any lack of effect could be blamed on the age or concentration of the cure-all. Treacle's mistique and association with ancient esoteric texts may have helped its reputation. Honey and opium can't be entirely unpleasant, even if mixed with bitumen and roast viper.

Astrology

Knowledge of practical astrology was vital for medieval physicians. The time and place of treatment could only be determined by careful examination of the stars and their effects on the humours of mankind. Using astrology for medical purposes was tolerated. Using it for predictive purposes was dangerously close to witchcraft.Since astrology is also a total system - it is self-contained, difficult to directly disprove, and willing to absorb criticism - it is difficult to use in RPGs. Making up new constellations and their attributes, then adding fake planets, tends to result in pages of tedious background information. Using "real" astrology for a fictional world seems anachronistic, like having Wales next to Faerun.

It's difficult enough to remember to use weather in D&D-type games. Astrology seems like one more thing to forget to track.

Retroactive Identification of Causes

In October 1348 Phillip VI of France requested the faculty of medicine at the University of Paris provide him with a consultative document explaining the causes of the Black Death, then endemic throughout his kingdom. The ensuing report, which was drawn up by some of the leading medical authorities of the day, and represented the most scientific thinking in Europe, unequivocally - and perhaps conveniently - attributed the outbreak and severity of the disease to circumstances beyond the control of any human agency. Indeed, the fate of its victims had already been decided at one o'clock on the afternoon of 20 March 1345, when there took place

an important conjunciton of three higher planets in the sign of Aquarius, which, with other conjunctions and eclipses, is the cause of the pernicous corruption of the surrounding air, as well as a sign of mortality, famine, and other catastrophes...The conjunction of Saturn and Jupiter brings about the death of peoples and the depopulation of kingdoms, great accidents occuring on account of the changes of the two stars themselves... The conjunction of Mars and Jupiter causes great pestilence in the air, especially when it takes place in a warm and humid sign, as occured in this instance. For... Jupiter, a warm and humid planet, drew up evil vapours from earth and water, and Mars, being excessively hot and dry, set fire to these vapours. Whence there were in the air flashes of lightning, lights, pestilential vapours and fires, espeically since Mars, a malevolent planet generating choler and wars, was from the sixth of October 1347 to the end of May of the present year in the Lion together with the head of the dragon. Not only did all of them, as they are warm, attract many vapours, but Mars, being on the wane, was very active in this respect, and also, turning towards Jupiter in its evil aspect, engendered a disposition or quality hostile to human life.-The Black Death and Men of Learning, A.M. Campbell, quoted in Medicine & Society in Later Medieval England, Carole Rawcliffe

Since we are currently in the middle of an epidemic, I'd like to commission any bored individuals with knowledge of astrology to check for unwholesome conjunctions in Wuhan between 6 October 2019 – 11 December 2019.

I've tried using sites like this one, but they require a degree of specialized knowledge I can't be bothered to obtain. COVID-19 is obviously a phlegmatic disease (cold, wet, associated with the lungs and lethargy), so that's a good starting point. It is extremely odd that these two plagues are both associated with the 6th of October. The only other plague I can find that began on October 6th is Instagram.

Coincidence?

Yes, coincidence. But still. I'll send a free PDF of MIR to the person who produces the most coherent, fully cited, and comprehensive astrological origin for COVID-19.

I've thought many times about incorporating humoral theory into RPGs (and did squeeze some in one time in a fantasy setting for Hero System). Since any disease system for a game is going to be only a small cross-section of real world diseases, and since medicine at the times most often replicated in fantasy gaming was almost all art and very little science, the best way to work it into a game is just to build the disease table around the humors rather than trying to grab a bunch of actual data on real world diseases and trying to shoehorn the humors into it.

ReplyDeleteUgh now I really wanna try making uroscopy gameable just to see if it's possible

ReplyDeleteIt might be possible to make a uroscopy system.

DeleteGetting anyone to play in a game with a uroscopy system might be more challenging.

As with all things, award XP for meaningful use and you'll have players falling all over themselves to peep that wheatgold tonic.

DeleteNot sure if this warrants the MIR prize as I found it rather than wrote it, but hopefully that counts as "produces"? In any case I got a good laugh.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.horoscope.com/article/coronavirus-update-the-astrology-of-covid-19/

It will certainly do. What's your email? Or send me a DM with it on twitter or discord.

Delete