This post is a medley of ideas that didn't make it into full post development, but which still deserve consideration. It's a scrapbook.

Part 1: Flight

Access to reliable flight changes a game. Overland exploration becomes trivial. Running away from a fight becomes far easier. The GM has to pivot to air-based encounters, which can be frustrating. It's hard to build interesting kinetic arenas in the air. Over the years, games have tried various methods to limit flight's appeal.

Most of these issues are covered in the AD&D DMG (pp. 50-53), but from the D&D-as-a-wargame perspective.

Limited Duration

In OD&D and AD&D, the fly spell lasts [level]+1d6 turns, with the 1d6 being secretly rolled. This makes planning difficult, but flying casters can always err on the conservative side. Flying creatures have to rest and eat.

Limited Speed

OD&D doesn't have the most consistent rules when it comes to flight duration and flight speed, but the gist is that flight is slow (by aircraft standards). Ask any pre-modern general if they'd like a high-altitude scout or courier that ignores terrain and can travel 10 miles per hour for several hours on end and they'd start to froth and salivate.

Limited Capacity

"Can a wizard with fly cast on them carry another person?" is one of those perpetual GM rulings. If the spell can lift a 200lb wizard, can it lift 400lb at half speed? 2,000lbs at 1/10th speed? Will the effort pull a wizard's arms off? Can one person ride on their back and fire a crossbow? Can the wizard fly upside-down?

Flying carpets typically become mobile casting platforms, a sort of dungeon helicopter. Flying brooms are most useful in pairs, with a sort of loot hammock between, ideally occupied by a rascally urchin, a lantern, and a crossbow. Or maybe that's just my groups.

Setting Concerns

The GM can present a compelling reason why long-distance flights are unwise. In the Ultraviolet Grasslands, shards and wires of ancient force fields dot the landscape. Skyhooks, shattered shields, miscast spells. At ground level, they tend to accumulate debris and turn into hills or pillars, but in the sky, they're invisible hazards. And so, very few aircraft exist.

In by-the-book classic fantasy settings, players might be disappointed if the GM introduces high-altitude mosquito swarms, jealous lightning-wielding gods, and or 50' thick atmosphere to prevent flight.

Part 2: Flying Machines

Fairly early in D&D's evolutionary history, players started making airships. The process was eventually codified, but enchanting sailing ships and trying to invent the hot air balloon are old traditions. Airships are great. A convenient mobile base to satisfy the base-building furnishing-orientated players. Conventional wisdom says a game becomes a pirate game the moment the PCs acquire a sailing ship. An airship lets the GM use standard dungeon/land-based adventures.

Rapid long-distance travel is covered by teleportation spells, gates, or restarting a campaign with new characters in a new setting.

Small fast flying machines do not have a niche in D&D. Brooms, carpets, mounts, and spells cover the typical combat use cases. Without a long-range machine gun, an airplane is a expensive way to deliver a crossbow bolt somewhere near a target.

Yet there's a delightful period of aviation history between the discovery of stable flight in 1903 (ish) and the pressing needs of war in 1914. To most people, a biplane is a biplane, but the variety of workable (if we're being generous) designs before the First World War is astonishing. This site lists most of them.

To make a plane, you need:

- A method of 3-axis control.

- A light power source. Steam engines and springs are too heavy.

- -Some basic knowledge of aerodynamics.

If you can read, weld, and do algebra, you can probably make a functional plane that will get off the ground. The trick - as many pioneers found out - is control and stability. Up is easy; up and then immediately nose-first or sideways or back over is almost inevitable. It's probably best to buy a kit... or avoid the whole hobby. All the kit planes are designed to fly at sensible altitudes and useful speeds, while a 1910s replica is basically cross-country cycling with added danger. At low speed, the difference between flying like a kite and falling like a brick is a strong gust of wind.

Also, don't get your airplane-building advice from RPG blogs.

In a typical RPG setting, planes can't stay at the 1903-1914 pioneer phase. Settings are designed to be timeless and static. Technology does not change, outside of the occasional mad scientist type (who usually shares the same fate as their inventions). The timeline covers centuries. But in Magical Industrial Revolution, the setting is designed to progress, over a relatively manageable number of years. Powered flight can flourish in such a setting, if your players are so inclined.

|

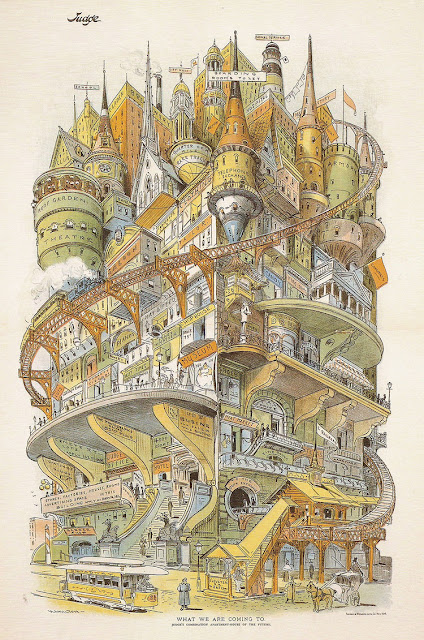

| Judge Magazine, Feb 1895. Colourized. Side note: Judge Magazine's early issues are very racist. You've been warned, but you're not prepared. By the 1920s, it's become a slightly edgier Readers Digest or Life magazine. |

Part 3: Deliberate Development

One of the eight Innovation tracks in Magical Industrial Revolution covers the development of personal transportation. "Miras" are car-like vehicles powered by moveable rods. They don't drive. They bounce, then featherfall.

|

| Mira by Logan Stahl |

This is fairly insane way to design a vehicle, but that's the point. Putting wheels on a Mira is something the players could attempt (though inventing brakes might be wise).

By making a bouncing vehicle, I wanted to gently steer GMs towards unconventional civic development. Endon has carts and carriages; a horseless carriage suggests the same development arc as motor cars in this world. Traffic signals, intersections, crosswalks, highways, etc. But Miras aren't cars. They bounce. What do traffic signals look like? Are there designated landing and departure lanes or spots on each street? How are existing structures altered to meet the growing demand for personal transport? In the real world, cities turned themselves inside-out to accommodate cars and trains. What will your Endon look like?

Part 4: Buxton Beach

Very early in Magical Industrial Revolution's development, before the project had a name or a theme, I considered adding a Coney Island/World's Fair/boardwalk area a sort of adventure-exhibit hub. The idea never went anywhere for a few reasons, including (but not limited to):

- It didn't fit with Endon's London pastiche.

- It didn't serve any real purpose for adventuring groups.

- Rides and attractions tend to rely on GM descriptions without presenting any interesting choices.

- World's Fair exhibits feel like sanitized and saccharine versions of living, vibrant innovations, packaged into a propagandized form for mass acceptance. I wanted Endon to be about the messy process of a revolution, not about the telegraphed reports.

- 1890-1910 Americana felt a bit too much like Bioshock: Infinite.

And so the idea was cut from the next planning diagram, but it might be worth revisiting on the blog, where ink is free and ideas don't have to fight to survive.

Half an hour downriver, or an hour by omnibus, Buxton Beach is the play-ground of Endon's Lower and Middle Classes. The Upper Class have their own estates (or aspire to them), and can afford to leave the city during the Off-Season to enjoy clean rural air. The Poor can't afford the price of admission, but it's an accessible dream. Both nevertheless seep into Buxton Beach. It is a dream-world, where people can escape their lives and the conventions that bind them.

Attractions

Also see this map.

Bessy the Mechanical Cow

Ejects fresh ice-cold milk from her mechanical udder.

Panoramic Orbisphere

A huge hollow sphere, painted on the inside with a map of the world (speculative). Induces vertigo.

Tableaux Vivants

History, comedy, and literature, plus the most tasteful nude and erotic scenes from history and

mythology. Scholars at Loxdon College can earn a few coins by scouring

ancient texts for suitably obscure novelties.

Miniature World

A tiny city with tiny houses and (if the shrinking spells work) tiny people in tiny costumes. Shrink down for your shift, unshrink at the end of the day... hopefully.

Roller-Coasters

With stable short-range portal spells, roller-coasters can cheat gravity and borrow momentum. Surprisingly safe, if the occupants are sober.

Seances

Dread Necromancy is illegal in Endon, so those who trade in false hope and monetized grief must advertise their arts subtly.

And also: Bathing Machines, Brothels, Bear-Fights, Exhibitions from Foreign Parts, Novelty Undergarments Sold Discreetly,

Part 5: Appendix N:1890s-1910s

The American Experience: Coney Island (1991)

About as much to do with American history as my medieval history posts

have to do with medieval history. It's a summary, propaganda, nostalgia.

Accurate in broad strokes, wildly inaccurate in detail, more interested

in coherence and convenience than in the facts.

This documentary from Defunctland is more accurate, funnier, and more nuanced.

Side Note: I've always maintained that theme park design and RPG book design have a lot in common. I send this post on Weenies to people on a regular basis.

I vaguely remembered watching this film, dismissing it as "unconvincing composite shots of matchstick models", and never revisiting it. I think it must have been the print quality or something, because, rewatching it recently, it's exactly the sort of thing I love. Ambition and folly. Sure, it's the sort of film that makes Jeremy Clarkson tumescent with nostalgia and imperialism, but they built the planes.

They actually built the planes. And then they put pilots into them and flew them, and all the pilots lived. And they all had a great time. You probably couldn't do that these days, but safety hadn't been invented in 1965, making any stunt inherently safe.

The Iceman Cometh (1973)

A very long time ago, I picked up this film by mistake, thinking it was "Encino Man". I was in for quite a surprise. The Iceman Cometh is four hours long and has two intermissions. I'd suggest going in without spoilers. I don't know if this play is one of the ones inflicted on indifferent schoolchildren in some parts of the world, but if it isn't, and you're seeing it for the first time now, you're in for a treat.

I was only aware of the director, John Frankenheimer, from Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau, where he shows up to salvage the disastrous film project. In the documentary, he's presented as a tyrannical workhorse, the studio's idea of a US Marshal sent to clean up the town and restore law and order. All craft and practicality vs. Stanley's impractical but artistic vision. It's interesting to see the other side of a director.

The Iceman Cometh takes place in 1912 BCE (Before Conditioned Environments). It's a hot and greasy era, and few films make it feel as suffocating. It's also an old film made cheaply, and most of the commercial versions aren't taken from great prints, so there are fun colour jumps and noise.

The weird part is that it's not the only film from the '70s set in the early 1900s that's 4+ hours long.

Flight of the Eagle (1982)

Slow, Swedish, and tangentially related to the themes of this post, but if you want to see a full-scale balloon and some folly and ambition, this film might interest you, especially if your players want to explore unknown regions via balloon.

And The Ship Sails On (1983)

Barely qualifies, as it's set in June 1914, but it's by Fellini and it's good. Not, perhaps, a work of genius, but it's charming and eccentric. As with Boris Godunov (1989) or Anna Karenina (2012), everything is a set. Since RPGs operate on the same sort of logic, it's useful to see it in practice.

There Will Be Blood (2007)

Famous and immensely quotable

Top Ballista came out in the Basic-D&D-is-goofy era with magically-powered biplanes fueled by fire magic (whether fireball, a summoned fire elemental, or what-have-you). I think particularly for MIR, the intensity of fire magic could serve as a limit on technomagical flight, with readily-imagined dire consequences for mishaps during research.

ReplyDeleteCompetitive Mira driving could also be interesting, since you could have speed/distance competitions, endurance competitions, and precision competitions (who can align the closest to a chalk outline on a target?). There's also the potential to experiment with them for flight, if the cycle time for the moveable rods can be made fast enough that you don't lose all your altitude feather falling. Of course, the problem then is what happens if the feather fall no longer lasts long enough to reach the ground safely...

How have I not heard of Top Ballista before now? Oh dear!

DeleteI feel like there are safer options for motive spells than fire, but a few wizards who will probably try anyway.

I'm hoping to include competitive Mira races in the next game. Possibly in a bootlegging / foolhardy student context.

Have you read the Edge Chronicles by Stewart and Riddell? Very good take on a smorgaboard fantasy without being overkill, with a constant theme of fantasy flight across different eras with different "technologies".

ReplyDeleteI think I've read a few of them. They're the ones with the lighter-than-air stones and condensed lightning, right? Good stuff.

DeleteRe not fitting with the London pastiche, what about: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Exhibition

ReplyDeleteAh, but that's a) High Victorian, b) the wrong time period, c) unthemed (other than maybe Hooray Imperialism), and d) didn't have a midway.

Delete