|

| Paul Pepera |

Unexpected Desirable Outcome

They’d let him name his ship. He picked “Hope”, after the virtue and after his sister. Translating Hope into Galactistandard was difficult, but they’d settled on “Unexpected Desirable Outcome.” A few alien consultants politely pointed out that if you didn’t expect an outcome, your prediction system was poor. Why would you admit that? But Wyatt liked the self-effacing implications.

UDO, his custom-trained voice assistant, woke him up three hours early with a non-emergency tone. He stuck an arm out of his sleeping sack and tapped at the nearest screen. A long transmission in Galactistandard appeared. An open broadcast, but it specifically named his vessel, along with every other vessel in system. The automatic parser had run into real trouble. Large portions of the message were highlighted in speculative yellow, and a few clauses weren’t translated at all. Wyatt switched to the raw Galactistandard, sighed, and got to work.

‘Hzoc’ is the species name. “Explorer Individual Hzoc Letien” right, that’s odd. Starts with a disclaimer, Request, no consequences. So even reading this doesn’t require a response of receipt. Dum dum dum dum... Request assistance... what’s this word? I’ll come back to it. Request assistance something something something manipulator size.... under 154cm total... I think that’s followed by...

Thirty minutes later, with a great deal of cross-checking, Wyatt worked it out.

“Medical assistance. Hzoc Letien is in

medical distress and needs help. The issue is on the upper side of its body.

The issue is physical in nature. The issue will kill them. The issue is not

complex. Further instructions can be provided,” Wyatt summarized aloud.

The Orlo vessel Large Reflective Grub, the scout ship that had picked up his Hitchhiker Waiver and hauled him into this system, had already responded. “Reply: unable to assist. Clarification: regret.” Wyatt stared at the word.

Galactistandard did not make regret easy. If you took the time to respond to a message that did not ask for a response, said you were not going to help, and did not clarify why, then the regret was built into your response. To state it again was, as far as he could tell, an intensifier. Galactistandard was a language, not a physical law, and species used it in different ways. Even if the Orlo could help, the Large Reflective Grub was several thousand kilometers away, coasting towards another station in the ring of factories and solar collectors dotting this system's asteroid belt.

Could anyone else help? The Orlo were too far away, and the only other non-automated ship at this station was occupied – or, more accurately was – a hibernating Downlink Ball, waiting to be picked up by another ship in a few decades. Maybe he should have spent some time greeting the Hzoc, but he’d been enjoying a long conversation with the Orlo.

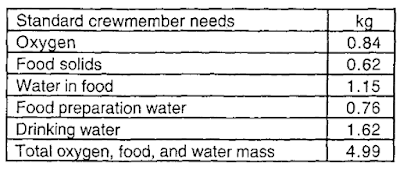

Wyatt opened the file on everything Humanity had recorded about the Hzoc. It wasn’t much. No images. No recorded contact. No connections. No rumours. Their habitability code listed a methane and nitrogen atmosphere at 0.3 bar and 45 degrees C. Not breathable... but workable. He could stick his bare arm into that without any issues, not that he wanted to.

“Reply: Human Explorer Individual Wyatt Anvar. Acceptance: tentative. Request clarification procedure. Request: tutorial. Request: images.” He copied in the standard human wavelength and resolution codes and sent the message. It wasn’t good Galacticstandard, but he hoped it would do.

“Fuck it,” he said out loud. He had no idea how long Hzoc Letien’s medical distress would continue before death, or its equivalent, intervened. They could already be dead. But it was him out there, he’d want to know that someone was at least trying to help. Wyatt brought up a system map. Hzoc Letien was docked to the station, on the same shadowed side but further down. Over a kilometer away. Invisible, at least to his eyes. Wyatt switched to the flight control panel, tapped the “undock and reposition” button, scrolled through the checklist, and confirmed.

UDO turned off the magnetic plate and automatically pulled through the mooring wire. Wyatt thought about how lucky it was that hadn’t set up umbilicals or a more permanent connection. In under a minute he was free, typing a flight path frantically into the console. Slow, steady, and radar-guided. He locked rotation and distance to the station’s arm and puffed sideways at just over 2 metres per second. Above, blinking through the window, he could see UDO’s navigation light pulsing a general warning signal in Galactistandard. The randomized pause between code-pulses made it impossible to mistake the pattern for light glinting off a rotating ship.

A reply from the Hzoc, and it was a complicated one. Wyatt watched the parser chew on the files. A video! This was something new. He opened the file. The video was low resolution, around twenty seconds (if the parser had calibrated it correctly), and had no sound. A blurry blob in darkness. He fiddled with contrast and brightness settings, then replayed the file. Much better. Hzoc Letien was a green-grey... lump.

What’s the scale? If that’s the interior of the ship, it’d be about the size of a cow. Four limbs? The pod looked just as crowded as UDO, with curved metal panels and soft bundles of who-knows-what. He watched the creature move around the pod, brace itself against the walls, and loop two limbs around something unseen. Whatever it was pulling came free suddenly. The alien flew back. It collided with the edge of an open panel and flung its limbs out in a gesture that Wyatt interpreted as agony. The sharp edge of the panel had gouged a deep wound in the Hzoc’s back. No matter how it positioned its limbs, it couldn’t reach the wounded spot. Wyatt watched the video again. Pull a little too hard and something snaps, he thought. Could happen to anyone.

The message also contained a sequence of black-and-white images, presumably copied from the equivalent of Hzoc anatomy textbook. Lines, diagrams. Instruments. A clamp-like thing with grips like the end of a whisk. A blade. And, astonishingly, what seemed to be sutures. From the images, Wyatt finally acquired a firm sense of the Hzoc’s form. Six limbs, not four. Starfish-like. Two limbs, what Wyatt decided to call a “head” and “tail” were unique. The other four were identical. The four main limbs ended in filaments or ribbons. The underside of the Hzoc’s body didn’t contain a mouth. Not a starfish then, a plesiosaur, with fat flippers and a very short neck and tail.

The creature had no skeleton, just a series of plates along its back, under its skin... or its suit? One or more of those plates had shattered. The sharp edges were, presumably, digging into its flesh every time it moved. Was it just in pain? No, it had mentioned death. Perhaps the injury threatened the bladder system that ran through the creature. A few phrases from the initial message made more sense. The Hzoc were vacuum-adapted. If its skin couldn’t seal, it couldn’t leave its ship. All he needed to do was remove the broken plate or plates, then ladder-stitch the outer layer shut.

Wyatt flipped back through the messages, then spotted a little red warning dot at the end of the Hzoc’s atmosphere list. Methane, nitrogen, formaldehyde, not great, hydrogen cyanide, very bad, and in bright red, chlormethine. He tapped to expand the entry and was greeted with a wall of red text. Blistering. Death. Slow death. Fast death. Horrible full-body symptoms. What sort of insane biology produced chlormethine? The atmosphere code doesn’t list a percentage. Was it trace? A temporary product? Could he count on that?

“No leaks,” he mumbled. “And even if I could get my EVA suit into the Hzoc ship, and it didn’t dissolve or explode, I can’t do surgery with those thick gloves. The robotic arm? Maybe, but it’s not designed for atmospheric use either. I could wrap it in a bag, but then...”

Wyatt sent off another message. “Acceptance: continuation: tentative.” The grammar check lit up in yellow, but he hit the override and plunged on. “Request: time to death.” Galactistandard did not have a lot of room for bedside manner. “Request: tutorial: airlock Hzoc Letian vessel.”

The Hzoc vessel was visible now in the faint glow of UDO’s navigation lights. A long cross-braced arm covered in radiators, and fuel tanks and a nuclear reactor at the far end, with a pressurized grey cylindrical module attached to the station. It was hard to gauge its scale visually, but the screen showed that the pressurized segment alone was three time the size of the UDO. No windows, just the usual collection of lumps and aerials and ports.

“Reply: imprecise estimate: time to death [3 hours],” appeared on the screen, followed by a series of images. Hzoc technical drawings were even less comprehensible than their anatomical drawings, but the airlock seemed to be a sort of sheet or membrane. He’d seen a similar device in training; other species apparently used similar technology. An inch-thick sheet of goop with reinforcing strands running along one direction. Objects could slowly push their way through a sealed slit in the middle of the goop. Contiguous objects only; a pipe would still let all the air out.

The autonavigation system chimed, nulled velocity, checked for anything that might the hull, and carefully swung the UDO’s stern around, dropped and locked the magplate. The suitport was less than 10m from the Hzoc airlock.

“Not bad,” Wyatt said. “I’m here. Now to do something useful. Come on, brain.” He didn’t feel like a steely eyed missile man. He felt helpless and tired and stupid. In order to help, I need to get my arms into that capsule. The airlock design will help. Option 1, I use the EVA suit. Can’t use delicate tools. Wait, I can’t use the Hzoc tools at all, I think. Wrong finger shape.

He tapped out another message. “Inquiry: Hzoc atmosphere biology general react polytetrafluoroethylene, [stainless steel]?” and let the auto-parser chew on the statement for a few moments, converting English nomenclature to grammatical strings of Galactistandard. If Hzoc biology ate teflon, there wasn’t much he could do. Luckily, the response came back negative across the board.

Option 1, he mused. EVA suit arms in a Teflon bag. No dexterity. Option 2, robot arm in a Teflon bag. Even worse. Option 3. Give up. Option 4...

Teflon bag. Why had that popped into my mind all of a sudden? Teflon bag...

“Oh that is dumb,” he said aloud. “That is very, very dumb.”

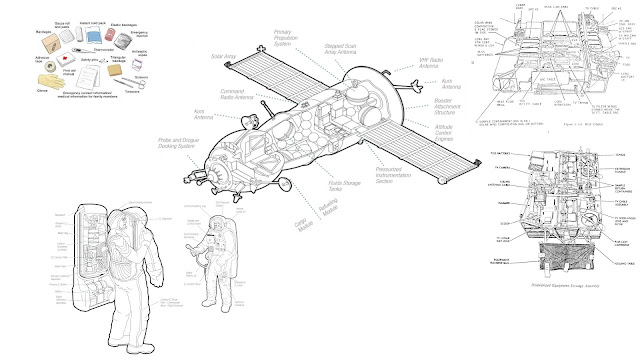

He opened up the life support menu and initiated a depressurization program, from 1 bar down to 0.6 bar, and with extra oxygen cycled in. He set his EVA suit’s baseline values identically, but with a pure oxygen mix, even though the suit’s systems were currently dormant. As UDO’s fans spun up, he popped open the surgical kit, took out a handful of stainless steel instruments, and stuck them in a plastic pouch.

Sutures, he remembered. What are the chances human surgical thread is compatible with Hzoc biology? Zero. He opened the image of the Hzoc surgical tools, added a marker and boundary box, and sent it back with the note, “Request: make this.” He stuck the bag of instruments in the small sample airlock and cycled it to vacuum.

“Ok, Hzoc Letien, I have a plan,” he said. “Let’s see if I can describe it to you.”

Explaining a plan in Galactistandard had several advantages. It forced Wyatt to examine his assumptions, to check for ambiguities, to go through a procedure step-by-step. He gulped down oxygen-rich air as he typed, trying to push nitrogen out of his body. The plan made several assumptions, including that a species that put a nuclear reactor far away from their living space didn’t enjoy casually bathing in ionizing radiation, that a species that sent over diagrams and videos was, to some degree, sighted, and that Hzoc Letien wouldn’t do something violent or foolish.

Hzoc Letien accepted, tentatively.

Wyatt opened a storage pouch and drew out one of the extra-large teflon bags stored inside. The bag was milky white, but still translucent between bands of with high-tensile polymer wires. In training, he’d seen one of these bags hold 1 bar of pressure in vacuum. Sealed with the locking plastic flaps and with tape, of course, but it held. If an alien wanted an in-situ sample of something from a pod, but the sample didn’t fit in a vial or jar, then a bag could, in theory, work.

He also grabbed a roll of sealant tape, slapped an anti-nausea patch on his arm, and started UDO on the pre-EVA checklist.

The suitport was a small airlock, bigger than the breadbox-sized sample airlock, and just large enough to fit one very uncomfortable human. The inner door was a plug door, designed to seal under the pressure of air in the pod. The outer door was locked against the back of the EVA suit, and opened inwards, into the tunnel.

Wyatt stuck his head into the space, opened the outer hatch, and began carefully taping the bag to the top of the ring of metal on the back of the EVA suit. He carefully creased the tape with his thumb. No gaps, no air bubbles.

After ten minutes, he retreated, then entered the tunnel and EVA suit feet-first, the correct way, sealing the inner door behind him. Working blindly this time, he taped the rest of the bag to the edge of the suit’s entryway, leaving a gap by his left kidney. Slowly, letting air escape through the gap, he pulled the bag in behind him until it was wedged in the small of his back, then closed the EVA suit’s door. He sealed the last bit of tape, rearranged his arms into their arm-holes, and checked his helmet displays. Everything looked good. Suit pressure of 0.6 bar, pure oxygen mix. “UDO, EVA door seal check,” he said. Servos whined as the door flexed inwards.

“Sealed,” UDO

reported.

“Decouple suitlock,” he said. The bolts around the back of the suit retracted. The inner plate of the door stayed attached to the ship, while the outer plate was attached to his back. He reached over and gently undid the clamp connecting his backpack to the ship, then, with great care, swung it closed. It clicked against his back, and a new set of lights blinked green in his helmet.

He turned and carefully opened the tiny sample airlock and removed the bundle of surgical instruments. Finally, he unclipped the safety line and, with one hand always clinging to part of his ship, climbed down to the enormous trusses that composed the arc of the station. The Hzoc ship isn't to port, he thought, it's up. And up he climbed. He could have pushed off and drifted, but what if he missed, or started to tumble? Even with the gyro in his backpack, it was too great a risk. His maneuvering pack could have puffed him over instantly, but it was another system that could easily fail. Best to minimize the risks, not compound them.

“UDO, cycle the air in the suit. Maintain pure oxygen mix, 0.6 bar,” he said. Better to lose some air and try to get the last bit of nitrogen out of his blood than to die in of a stroke. He could see a faint white cloud in his rearview camera as UDO flushed the suit, the hiss of new air entering, then silence.

The Hzoc ship was lightly textured, as if the outer shielding had been knit from thick wool and then sprayed with white paint. The airlock, or gooplock, was just above the station’s scaffolding, surrounded by the half-embedded rings he’d seen in the diagram. The outer protective door was open, as, to judge by the extremely faint light visible through the rubber-like sheet, was the inner door. Wyatt could see nothing inside the ship.

“UDO, switch radio to band 44,” he said. He could try tapping on the hull, but transmitting on the Hzoc’s frequency seemed quicker.

He clicked the press-to-talk button on the front of his suit. “Greetings: formal: Human Wyatt to Hzoc Letien” he said in rapid but carefully enunciated Galactistandard. “Declaration: location of this one is adjacent to airlock. Request: this one enter.

The Hzoc transmitted back and UDO read out the text. “Acceptance.”

Wyatt was surprised to feel a brief flicker of anger. He realized that part of him had hoped the creature would deny entry, or be dead already, or have come up with a better plan, or revealed that this was all a test put on by the Orlo or some other species. He knew it was just part of his mind looking for a way out. No way out now. He could always leave, of course... but who would he be if he left?

He pushed the bag of surgical tools into the goop, marvelling as they sunk through the layer of mysterious gel. Was it biological? Some extremely fancy polymer? The shadows inside the pod shifted.

“Tools,” Wyatt transmitted. No time for grammar.

He turned around carefully, facing his backpack towards the airlock. “UDO, unclip backpack lock,” he said. He swung the backpack away from the suit, locking it to his left in the position normally used for maintenance or docking.

“UDO, hold command. Set the desired pressure of the suit to 0.3 bar pure oxygen, but do not depressurize,” he said. “Repeat that back to me.” UDO dutifully repeated the instruction. “Perform command,” he said, and watched the indicator on his display reset, while the measured pressure remained constant.

Reaching to the bundles of tools on either hip, he clipped his left safety line to one of the rings around the airlock, clipped his right safety line to the opposite side, then repeated the process with his two utility lines.

“UDO. Hold command. Open EVA suit door.”

“Invalid command,” UDO said, “EVA suit is not docked. Opening the EVA suit door will cause the suit to depressurize.”

Oh no it won’t, he thought, because I have a teflon bag. Assuming the tape holds, and that it expands into the airlock, and that the bag doesn’t pop. What a stupid way to die. Here are the mummified remains of Human Explorer Wyatt Anvar. He stuffed himself into a trash bag. We don’t know why. Heh. Heh heh heh. Is this nitrogen narcosis? No, wait, the pressure is dropping, not rising. Get it together.

“Override. Hold command. Open EVA suit door.”

“Override accepted.”

“Request: Imperative: position Hzoc Letien to airlock increase to maximum. Position tools to airlock increase to maximum,” he broadcast.

“Acceptance,” came the response a moment later.

Wyatt pulled his arms out of the gloves and wedged them against his sides, then pulled his head down and hunched over. He wiggled to line himself up with the rearview camera, just barely visible if he looked up and into the helmet. “UDO, perform command,” he grunted.

The door swung open and slammed into the backpack, hard enough to rattle Wyatt’s teeth. He stretched backwards, like swimmer bouncing off the wall of a pool, pushing the bag towards the airlock. Alarms beeped frantically as the pressure dropped like a stone. Wyatt’s left knee flared in agony.

Directed by Wyatt’s arms, the bag slid into the airlock. “UDO override retract all lines,” he said, and the EVA suit’s servos began cranking the braided steel lines back onto their drums, forcing the suit’s entrance flush with the gooplock. “UDO lock lines,” he said, when he felt like he was close enough.

Well this was a fine place to be, he thought. Half in and half out of an EVA suit, bent over backwards, in a bag, in the dark. At least there are no leaks. And I’m alive. Somehow. He could see the Hzoc ship only dimly through the bag and his new mildly bloodshot eyes. Hzoc Letien was flattened against the opposite wall, with the bundle of tools clutched in one set of tendrils.

“Greetings,” Wyatt said aloud. Just in case, he signed with one hand. He suddenly realized that this was probably the first time Hzoc Letien had seen a human. What an awful first impression.

The alien gently cartwheeled around the craft and touched part of a bulkhead. Wyatt couldn’t see what it was doing, but a moment later, a screen lit up, flickered, and settled on a black-and-white Galactistandard pattern. “Greetings.”

Non-vocal then. It might still be able to hear me, since it was able to understand and reply to my radio transmissions. But I can’t help if I can’t see, he thought, and those bumps looks like lights.

“Request: Increase radiation... blackbody full.” Wyatt said and laboriously signed. I hope that gets the point across.

The soft yellow glow slowly increased. When the pod was bright enough to see details, he said “Acceptance. Inquiry: acceptance.” Best to check if the Hzoc was comfortable.

“Acceptance,” flashed onto the display.

“Request: position Hzox Ld...” he signed, stumbling in his haste, “Request: position Hzoc here.” He wiggled his arms to show his limited range of motion, pinching his fingers together.

The Hzoc was larger than he’d expected, and as its bulk swung over him, he saw that its skin, or whatever coated it, was textured like asphalt. The cluster of red filaments on the end of each of its four legs, or what Wyatt had chosen to call legs, had a metallic sheen and square white tips.

And what was it using as an input device? A keyboard? He squinted at the bulkhead. More like an abacus or the volume dials on the front of my EVA suit. Strings of cylinders, rotating under the tendrils.

There’d be time for questions later. Hzoc Letien carefully positioned itself next to the bag. With the pressure inside the bag the same as the pressure inside the Hzoc vessel, Wyatt could, with great care, pinch and fold the bag enough to use the tools he’d brought over.

One of the Hzoc’s limbs passed over the bag. He saw, but did not feel, the filaments, move across the surface. Incredible control. Wyatt looked again. There was a black globe embedded in the softly tapered end of the limb, just above the tendrils. An eye? And was that little groove a mouth, a chemical sensor pit, or something else? He realized he’d have to revise his mental view of Hzoc anatomy yet again. Focus. Don’t anthropomorphize. See. Don’t project.

The Hzoc positioned itself very carefully, brought the arm with the tool bundle around, disassembled it, and handed a clamp to him. It was clearly reasonably intelligent and able to extrapolate. Wyatt stared at the jagged wound in the creature’s back tried to remember every step of the procedure. He was already sweating in the heat. The suit’s thermal system kept his legs cold, but his face was squished against 45 degree plastic.

It wasn’t difficult, just tedious and slow. The Hzoc’s skin had three layers: leather over rubbery sponge cake over a broken porcelain plate. With claps, forceps, and carefully drilled patience, Wyatt extracted splinters of glass and pushed them towards a waiting arm. Red tendrils caught the pieces and stowed them in a wall pouch.

Another arm passed him a cube of blue fibres, while yet another arm tapped out “Request: to liquid.” Assuming it was a sponge, Wyatt dabbed it along the wound. It seemed to absorb the clear oily fluid and leave behind blue flakes.

In training, he’d performed tasks like this (though perhaps not quite as difficult). He’d trained for frustration. Moving greased marbles with chopsticks. Rewiring a console in a vibrating, tumbling simulator. Mild torture. A hundred tedious, pointless, personalized tasks and tests designed to find and exceed his limits, so he’d learn to recognize and control fatigue, impatience, and fear.

“Request: tool. Clarification: sharp with long long...” but the alien was already handing him the pre-prepared Hzoc needle and thread. Brass, or maybe a gold alloy? The scale was wrong. It was smaller than expected, and he struggled to use the steel needle holder. His eyes burned with sweat. At least the stitching was easy. The outer skin layer didn’t tear or stretch. All the while, the Hzoc watched with one or more arm-eyes.

And then, finally, he tied off the last suture and passed back the needle. “Request: inspect this,” he gestured.

“Acceptable,” flashed the display panel. Then, more characters. “Request: place hexagon here.”

What hexagon? But the Hzoc was already extracting a package from a wall pouch. It carefully peeled a large hexagon covered in brown slime from a protective case, handed him a clamp, and positioned the sheet above the wound. Simple enough, he thought, as he did his best to position and smooth the dressing.

“Request: time to death,” he signed.

The Hzoc shifted away from him. “Reply: unknown,” appeared on the panel.

“Reply: Desirable outcome,” Wyatt signed back, grammar be damned. The Hzoc’s tendrils waved all at once. Wyatt had no idea what that signified.

He caught his breath and considered his next steps. Suddenly, despite the heat and the exertion, his blood turned to ice. He felt sick. He’d made a terrible miscalculation.

With the bag inflated, he couldn’t close the back hatch, and if he couldn’t close the back hatch he couldn’t dock to the suitport. Even if he had the strength to pull the bag back into the suit, it was coated in who-knows-what horrible chemicals from the Hzoc and its atmosphere.

This really had been a stupid idea. He stared at the Hzoc, and it, uncomprehending, stared back at him.

He’d have to leave the bag behind, but the bag was the only thing keeping air in his EVA suit. If he squeezed the door mostly closed, and then disconnected the bag... He was glad he’d laid down the tape stepwise, so it could theoretically be removed in one pull. He’d still have to pass it hand-to-hand, behind his back. Not ideal.

“Request: imperative,” Wyatt signed, after what felt like an eternity. “Grip this.” He pushed a fold of bag towards the Hzoc. With one set of tendrils, it cautiously grasped the folded plastic.

“Request: imperative: maintain position of this,” he signed. “Request: imperative: not inside airlock.” He gently slid back into the EVA suit while the alien held onto the bag with a firm grip.

“UDO,” he said, “unlock lines.” The four wires connecting him to the Hzoc hull flexed slightly, but friction on their drums held him in place for now. He turned to the right, twisting gently, cautiously, to give him enough room to shut the rear door. Not enough. He unclipped two of the lines.

“UDO, switch to override mode, and close rear door to 5 degrees.” 0 degrees was locked, 5 ought to be enough. Servos droning, the door slowly swung closed. Wyatt twisted gently to keep the bag from tearing away from the suit prematurely. He could hear air hissing through a few tiny gaps in the tape.

“UDO, hold command. 5 second countdown, then close and lock the rear door.”

While he’d never experienced decompression, it had been part of his training. He breathed rapidly, then said, “Perform command,” and exhaled hard.

“Five, four, three,” UDO dutifully counted. Wyatt swung his arms and legs back and tore away from the Hzoc ship. He couldn’t tell if the bag tore free or not. Air rushed around his ears. The door pressed against his back. The bolts clicked closed. Over the frantic beeping of alarms, he could hear the life support system trying to restore pressure. He opened one eye and checked the pressure gauge. It was holding. His ears ached, but he otherwise felt no worse for wear. He turned slowly. The bag stuck out of the Hzoc gooplock like a tissue in a tissue box, flat, deflated, and detached, with a ring of tape around the edge. Wyatt whooped with joy.

“Statement: Human Explorer Wyatt Anvar is alive,” he shouted into his mic. He spent a few moments catching his breath and satisfying himself that his suit was truly sealed.

“Reply: desirable outcome,” Hzoc Letitan replied a moment later.

“Request: imperative: release thin white object,” he said, tugging on the bag. It slowly emerged from the gooplock. He debated what to do with it. He couldn’t bring it back inside the UDO, but if he let it go his hosts would probably be annoyed. He decided to postpone a decision.

Half an hour later, he was back inside his ship, exhausted but alive. His EVA suit was down to less than 20% stored air, but he could top up the tanks in a day or two. It didn’t seem to have taken any permanent damage, save for a few scrapes on the titanium frame. The pain in his knee from his less-than-optimal decompression routine was slowly fading. Air mix in the living module was back to normal.

“Request: informal: conversation in [four hours],” he typed. He had a thousand questions for the strange being he’d just met, but he needed to rest, to check his own systems just as carefully as he’d checked the UDO’s systems.

“Reply: acceptable.”

Three weeks later, Hzoc Letien emerged from its ship, which Wyatt had learned was also named Hzoc Letien, and carefully trundled down the station truss, gripping with two limbs at all times. One of its non-eye limbs was half-embedded in a bucket-like device which served as a radio transmitter, light source, manuvering unit, and toolbox. Currently, it contained a bag full of carefully cleaned and sterilized human surgical instruments.

The Hzoc crept its way along the Unexpected Desirable Outcome’s hull and peered into the window with one black eye. Wyatt waved. The red tendrils, like a fringe of hair or a bushy eyebrow, waved back.